How Often Is the Emergency Disaster Review Form Completed

- Research commodity

- Open up Access

- Published:

Rapid Health and Needs assessments after disasters: a systematic review

BMC Public Health volume 10, Article number:295 (2010) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Publichealth intendance providers, stakeholders and policy makers asking a rapid insight into health condition and needs of the affected population later on disasters. To our knowledge, there is no standardized rapid assessment tool for European countries. The aim of this article is to describe existing tools used internationally and analyze them for the development of a workable rapid assessment.

Methods

A review was conducted, including original studies concerning a rapid health and/or needs cess. The studies used were published between 1980 and 2009. The electronic databasesof Medline, Embase, SciSearch and Psychinfo were used.

Results

Thirty-3 studies were included for this review. The majority of the studies was of United states origin and in nearly cases related to natural disasters, especially concerning the atmospheric condition. In eighteen studies an assessment was conducted using a structured questionnaire, eleven studies used registries and four used both methods. Questionnaires were primarily used to asses the health needs, while information records were used to assess the health status of disaster victims.

Conclusions

Methods well-nigh commonly used were confront to face interviews and data extracted from existing registries. Ideally, a rapid cess tool is needed which does non add to the burden of disaster victims. In this perspective, the use of existing medical registries in combination with a brief questionnaire in the aftermath of disasters is the most promising. Since at that place is an increasing need for such a tool this approach needs further exam.

Background

Importance of rapid assessments

When disaster strikes it is important to realize that apart from astute wellness problems that will be addressed by the emergency departments many other problems are likely to occur [ane]. Homes may be damaged, sometimes resulting in displacement of the population. Survivors might develop diseases or have other health problems as a consequence of the disaster. These bug may result in health related needs like medical treatment and medication use. Since a disaster might have direct consequences for public health intendance a clear overview of these health needs is important. Therefore rapid cess methods are needed to collect reliable, objective information that is immediately required for conclusion making in the recovery stage of the event. Health care agencies, stakeholders and policy makers will request a rapid insight into health status to take care of the needs of the affected population [2]. With this collected information almost wellness status and needs, public health interventions can be prioritized. Rapid cess tools are also important to guide the emergency efforts in the affected area [3]. For case, public wellness interventions and emergency efforts may include improvements of access to medical intendance, financial back up and restoration of damaged houses.

Since health needs can apace change [ii] afterward the astute phase and a quick insight into common wellness problems is of import to preserve adequate health intendance, this commodity focuses on cess methods which can exist applied in the first 2 weeks after a disaster. This is also important because collection of possible exposure data, such every bit the extent of involvement or the use of protection measures, is the most reliable in the first two weeks after an event (to foreclose recall bias). Furthermore, we presume that a rapid cess can provide information that tin be necessary in example the need for the regular local wellness and medical systems is unknown or if these systems are overloaded or disrupted due to the disaster. Later on all, if the regular local health care is operative no information is needed for collective health intendance.

History and background research

In the 1980'south the evolution of rapid cess tools started in the United States. In 1999, this resulted in the Rapid Wellness Assessment Protocols for Emergencies developed past the World Health Organization (WHO) [five]. These protocols were developed to determine the immediate and potential health bear on of a broad range of emergencies, such equally epidemics, natural disasters and chemical emergencies [v]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United states of america besides developed a rapid assessment tool to measure applied needs, health status and health needs [six, vii]. In kingdom of the netherlands wellness assessments after disasters so far focused on other methods, such as surveys with a time frame starting from three weeks to a few years mail service-disaster [8] and surveillance studies that were operational within a few months [nine, 10]. No standardized rapid assessment tool is available for the Dutch population and, to our cognition, for other European countries to assess expected wellness needs. This can result in failing to meet the bodily needs afterwards a disaster. Because emergencies are often circuitous, information technology is important to collect information systematically using a standardized tool [5].

Objectives and master goal

Which type of rapid assessment tools are developed and used internationally is the main question that forms the basis of this article, in which is examined which aspects of assessments may influence the rapidness such as training and procedure of cess. The chief goal of this article is to describe and analyze these existing aspects which volition contribute to the evolution of a useful rapid cess tool. With this review we will show what is internationally known in the literature and to evidence whatever possible gaps of information in the literature. Ideally a tool is needed which does not add to the burden of disaster victims. This is an important consideration when collecting health information well-nigh disaster victims. Nosotros volition hash out some aspects that might add together to or salvage this burden and view and compare the most normally used rapid assessments in this low-cal. This article focuses on assessment of health status and needs; however, when disaster strikes other consequences such as exposure that can influence the wellness of affected people needs to be considered and/or incorporated to minimize the burden of survivors and to restore their collective control [1].

Methods

Search strategy

To place the existing assessment methods in literature we conducted a systematic review. We started our search past defining search terms, which were categorized into four categories (table 1).

Five electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (NLM); EMBASE (2008 Elsevier B.V.); SciSearch (The Thompson Corporation); PsycINFO (AM. PSYCH. ASSN. 2007) and Social SciSearch (The Thompson Corporation). The categories were combined as follows: A AND B AND (C1 OR C2). We included scientific articles and books. The search was extended past examining references of the reviewed articles. In add-on to literature in the English linguistic communication, we included literature in Dutch and German. Every bit mentioned in the groundwork, the development of rapid assessment tools started in the 1980's. Therefore, we reviewed literature that was published betwixt 1980 and May 2009.

All titles and abstracts of the studies identified by the search in the electronic databases were screened by i of the authors to evaluate whether the inclusion criteria were met (H.K.). A selection of the abstracts was screened in a similar fashion by a 2d author (I. v. B.) to check whether the inclusion criteria were reproducible by a colleague researcher. Full text versions of all selected potentially relevant articles were judged (H.K.) confronting the inclusion criteria. In instance of incertitude, a second (I.v.B.) and or tertiary (L.Chiliad.) author was asked to evaluate these articles.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

i) Disaster criterion

Studies in the context of human-fabricated (e.g. explosions, aircraft disasters) or natural disasters (e.thousand. hurricanes, earthquakes) were included. In this study, a disaster is defined as a collective stressful experience with a sudden onset which causes disruption of a community. Studies most individual traumas, war, and drought conditions such equally malnutrition did not comply with this definition.

- 2)

Event criterion

Studies in which health status and/or wellness needs of disaster victims are the measured topics (table 2) were included. Health status includes the actual firsthand health issues and pre-existing health problems. This provides information to assess the immediate health needs of the affected groups. The focus of needs is on medical, housing and logistical issues. We included articles in which the health status and/or needs were actually measured. We excluded the studies if the assessed topics were not described.

3) Specific wellness status criterion

Studies that were included report the concrete health status like injuries and disaster-related diseases. Studies focusing exclusively on mortality or mental health disorders (in particular PTSD) of disaster victims were excluded. Mental wellness disorders are excluded, because they cannot be established within ii weeks, our definition of a rapid assessment, later on the disaster [11].

4) Population criterion

Adultsand children who were direct exposed to a human being-made or natural disaster were included. Relief workers were included; except if relief workers themselves were non straight exposed to the disaster.

5) Rapid criterion

Studies in which the assessment started in the start two weeks later a disaster were included. Our definition of rapidness in this review is two weeks, since needs alter chop-chop over time. If the cess was not performed within this catamenia, we included studies if the assessed method could have been used within this period. In lodge to determine whether this was possible we addressed the following questions:

-

Was the method or instrument (e.g. interview, surveillance) described?

-

Was the description available on how the assessment was conducted? (eastward.g. confront to face, an interview by telephone or self-reported questionnaires)

-

Is the moment (fourth dimension later on disaster) of measurement and duration of the assessment described?

A study was excluded when relevant information was absent to answer one of these questions. When information technology was obvious that the duration of the assessment was also time-consuming the written report was excluded. We did not use a clear cutting-off for the elapsing of a rapid cess, but when the duration was several months nosotros considered this also fourth dimension-consuming.

Data processing

The articles were grouped by the method of data collection. In this article we examined which rapid assessment tools are well-nigh unremarkably used. For each paper is described which aspects of assessments might influence the rapidness of an assessment. We distinguished the following aspects which possibly influence the rapidness of assessments: 1. Preparation of assessment, for example how a questionnaire is prepared (e.g. new checklist developed or checklist translated) 2. Time of cess afterward disaster iii. Details of method of data collection, for case how a questionnaire is administrated or how data is registered 4. Level of assessment (e.g. at individual or grouping level) 5. Source of data, for example who registered data and six. Location of cess. We will draw these aspects to be able to make well considered choices concerning the development of a useful rapid assessment tool. Furthermore we will search for a method which is the to the lowest degree enervating for affected people. Therefore nosotros will discuss and compare the results in the low-cal of a possible brunt of survivors.

Results

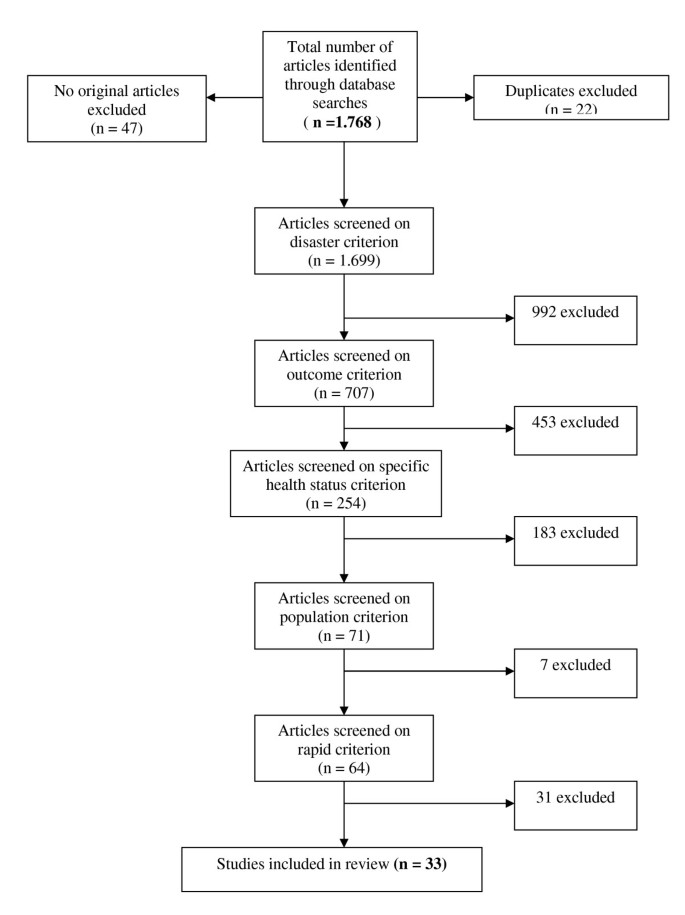

The search resulted in ane.768 titles, excluding 47 titles which were no original manufactures and 22 titles considering they were double in the search (Figure 1). Out of these 1.768 titles, 31 articles were excluded from this review because of the definition we used for rapidness. 33 manufactures were accepted for this review using our inclusion criteria. The accustomed manufactures were divided into two types of methods: structured questionnaires (n = 18) and registries (n = 11). Registries are systems in which routinely nerveless wellness information is registered. 4 studies used both questionnaires and registries to assess health status and/or needs.

Flow diagram of the reviewing process.

The topics measured were divided in four categories: demographics, health needs, wellness condition and practical needs (run across tabular array two). Structured questionnaires were primarily used to assess the health needs, while registries were used to assess the health status of disaster victims. All twenty-two studies which used interviews covered three or iv topics (22 demographics; 19 health needs; 22 health condition; 18 practical needs). Most of the studies which used registries (xiii/14) assessed data well-nigh health condition such as injuries and illnesses.

In 'Additional file i' and 'Boosted file two' for each report the type of disaster and the country in which the disaster took place is described, among other things. Disaster blazon was reported in order to examine whether there was an clan with the type of assessment used. The majority of assessments (31/33) were performed afterward natural disasters. The other two studies were reported afterwards man-made disasters. No association was found between type of disaster and type of assessment. Of the 38 assessments identified for this review, xiii were assessed after Hurricane Katrina (hundreds of thousands evacuees, 1836 fatalities). These assessments were at xiii different places and used different data sources such as disaster victims themselves, registries from military hospitals and registries from general hospitals.

Time of assessment

Data drove with the use of registries had on boilerplate a longer fourth dimension-frame than information collection with the employ of questionnaires. In table 3 the start of measurement combined with elapsing of information drove is summarized. Details about start time and duration can be observed in 'Additional files one & two. Nearly measurements (n = 29) started within the commencement two weeks postal service-disaster. Of these, 17 measurements started in the beginning two weeks had a duration which was shorter than one week. Nigh of these studies (fourteen/17) used questionnaires, in the other 3 studies registries were used. Ten measurements had a elapsing which lasted longer than two weeks; these assessments were performed with the use of registries.

Structured questionnaires

Twenty-two studies used a structured questionnaire as assessment method (Boosted file 1).

Preparation of the questionnaire

Development and preparation of a questionnaire is fourth dimension consuming. For rapid assessments time is crucial, therefore nosotros examined which aspects of preparation were present in the studies. The following aspects of preparation were distinguished: 1. Modification of a checklist 2. Translation of a checklist and 3. Design of a new checklist. In virtually studies (15/22) only one of these aspects of training was present. In three of these 15 studies [8, twenty, 27] multiple aspects of preparation were present which tin can be also time-consuming for rapid assessment (3/22). Nine studies used a modified checklist; eight of these studies used templates previously used past the CDC. 4 studies [8, 12, 15, 26] adult a new checklist after the disaster. In seven studies information technology was unclear whether an existing, modified or new checklist was used. Yet all of these seven studies were also performed with assistance of the CDC. Since viii studies performed by the CDC used a modified checklist, we assume these ix studies likewise used a modified checklist previously used by the CDC. In v [8, 17, 20, 24, 27] of the 20-two studies a questionnaire was translated, ii [20, 27] of these questionnaires were also modified to the specific disaster situation and 1 of them was as well newly designed [8].

Method of data collection

The style an assessment is conducted influences how rapid the information can be nerveless. The majority (20/22) of the questionnaires were administered face to face past means of an interview. One study [fifteen] used the telephone to collect information and in another study [8] the questions were self-reported by disaster victims. In near of the studies (17/22) in which face to face interviews were used information technology was unclear whether they used paper or digital versions of the questionnaire. None of the publications described their choice of information collection method.

Cess level

Rapidness of data collection tin also exist afflicted by the level at which an cess is conducted. Questioning all disaster victims at private level, for example, is more time-consuming than questioning at group level. In most of the studies (xix/22) in which a questionnaire was administered the head or a representative of the household was interviewed. In add-on to cess level, the full number of included survivors (respondents) affects the rapidness of data collection. Twelve (12/22) of the studies had betwixt 100 and 300 respondents, half-dozen (half-dozen/22) studies had between 300 and 500 respondents and three (3/22) studies had more then k respondents. The individually administered questionnaire had the most respondents (N = 3.792). In this study the researchers' goal was to include all survivors of the disaster [8].

Location of cess

In all twenty-two studies the disaster caused relocation of part of the affected population. In twenty (20/22) of these studies which used structured questionnaires the researchers made a visit to the residence of the disaster victims. Seven (vii/22) studies were performed in evacuee centres, thirteen (thirteen/22) in respondents ain homes. In one study (1/22) the disaster victims visited a research centre which was especially congenital [eight]. Finally, in one written report [15] there was no direct contact betwixt the interviewer and the disaster victims, because interviews were held by telephone.

Registries

Sixteen studies used registries to collect information about health status and needs (Additional file 2). Seven [25, 32, 34–37, 39] of these studies used more than one type of registry. In one of these seven studies iii unlike registration systems were used. In total twenty-4 different registries were used.

Method of data collection

We found two different data collection methods. In sixteen of these registries data was abstracted from existing registrations. Information was assigned into categories afterward the information was collected. In viii registries data was actively recorded on a specific standard disaster form. With this method, information was directly assigned to pre-chosen categories. In two [32, 35] of these viii registries health status was straight entered in a computerized disease registration arrangement. In 4 studies [36–38, 41] data was entered on a paper form. In the concluding two studies [29, 42] it was unknown whether data was entered on a newspaper or a digital grade. The majority of the sixteen studies that used regular registration systems did not mention whether these were electronic databases or newspaper hard copies.

Source data

In most of the studies (xv/16) data was registered by medical personnel independent of type of registration. In viii studies (8/15) registration was a standard procedure during medical treatment of patients. Seven of these (7/8) studies used Emergency Section (ED) logs reported past ED personnel. In eight studies (8/15) information was nerveless past medical personnel for purpose of injury and disease surveillance. In v of these (5/8) studies medical staff completed a disaster class for each disaster-patient visit. In two of these studies (2/8) a surveillance team itself completed the disaster class. In one study (1/8) it was unknown who completed the disaster from. Other medical records that were used were pharmacy records (ane/15) [35] records from a armed forces infirmary registration (one/15) [34] and records from a temporary medical service system (1/15) [25]. In iv studies [32, 35–37] both existing medical records and a surveillance grade were used. In the sixteenth study the Cherry Cantankerous household registration was used [14].

Assessment level

In 15 of the 16 studies which used registries the information was collected at individual level. These findings were collected at individual level simply reported at population level. In one study [14] the research level was a total household. In this study the Ruddy Cross household registration was used to provide household demographic information about the wellness needs of the households.

To get insight into the number of persons who tin be role of this type of inquiry (use of existing registrations) we examined the number of participants. Ii studies had between 200 and 500 participants, five studies had between one.000 and 6.000 participants, 4 studies had betwixt 10.000 and 25.000 participants and four studies had between 50.000 and 125.000 participants.

Comparison between the utilise of structured questionnaires and registries

We examined the clan between level of assessment with the blazon of assessment used (table 4). We found that type of assessment is associated with level of assessment. Structured questionnaires were mostly (20/22) assessed at household level and data from registries was by and large assessed at individual level.

Finally we observed that with the employ of existing registries comparison of health status in a disaster state of affairs with a not-disaster situation is possible. Half dozen studies compared data of registries with data from a reference grouping or reference period. In ane of these studies [25] information in the disaster area was compared with similar data from a normal registration system in a not-disaster area during the same catamenia post-disaster. 5 studies compared data of registries within their ain information (reviewed ED logs). 1 of these studies [28] compared data with the same period 1 year before, ane compared data from eight months pre-disaster with one calendar month mail-disaster [33] and one study compared the five days post-disaster period with the xx days pre-disaster period [32]. Two studies [29, twoscore] compared data of registries over i-week mail-disaster within their ain data over one-week pre-disaster. None of the data assessed using structured questionnaires was compared with data assessed pre-disaster or in a not-disaster situation.

Discussion and Conclusions

This review examined which rapid assessment tools are developed and used internationally. A distinction was found between the use of structured questionnaires and the use of registries for rapid assessment of wellness and needs afterwards disasters. Methods most commonly used were face to face interviews and data extracted from existing registries. Registration systems were used principally to assess health status of survivors while interviews were used primarily to assess health needs. Furthermore, we observed many aspects which influence the rapidness of assessment. Preparation and method of data drove seem to exist the most important aspects. Confront to confront interviews with the use of existing questionnaires was the most rapid fashion to collect data about wellness needs of survivors.

Influence of the observed aspects on the rapidness of assessments

When performing rapid assessments it is important that the time-frame of assessment is short, considering information gathering before long after a disaster is an important step in assessing the needs of affected people [43]. Several factors concerning these assessments have a potential influence on this time-frame. First of all the time of measurement after the disaster in combination with the duration of the assessment and the time it takes to procedure the results. The combination of these aspects determines in which time-frame ane tin share the nerveless information with health care agencies and policy makers. So it seems to be important for these agencies to know how soon later on the disaster the collected information must be bachelor in order to cull the most appropriate method. For case, when using information from registries it is of import to know over which period post- and predisaster information is available. When information becomes annually available this registration organisation obviously is not useful for rapid cess. It as well of import to know how much fourth dimension it will take to extract the data from the existing registries.

Using the rapid criterion we learned near some factors which determine the rapidness of an assessment tool. With this criterion we included studies in which the assessment was or could have been performed in the start two weeks later a disaster.

First we examined the reasons why studies (n = 9) did not start in the kickoff 2 weeks after a disaster but could have done and so within this menstruation:

a) Reason of convenience to collect data after. In i report survey data was collected at the same fourth dimension a charitable institution distributed monetary aid in emergency centres (> two weeks post-disaster) [xviii]. In two studies returned evacuees were interviewed who came back dwelling afterwards more two weeks post-disaster [15].

b) Reason of ethical regulation of study approval by a medical ethical commission. Due to ethical regulation survivors had to receive written information about the study [8].

c) Reasons of lack of preparation. In five studies questionnaires had to exist designed and or translated starting time [8, 12, 15, 22, 26].

Secondly, we examined why health and needs assessments (31/64) were excluded from this review because of the definition we used for rapidness. We examined these assessments in order to get insight into which aspects and how these aspects influence the rapidness of cess. In twelve studies (12/31) it was clear the method used was also fourth dimension-consuming. For example, the length of the questionnaire was likewise long (took one and a half hour to complete) [44]. Other studies, for example performed medical examinations [46–49] collected blood and urine [45] to assess the health status or performed vaccination measures [l] in improver to interviews. These fourth dimension-consuming extra wellness measures are not favourable for rapid assessments. Nigh of these articles (19/31) were excluded because relevant information was absent to decide if the assessment was rapid or possible within two weeks mail-disaster.

From the studies that were included in the review we observed several preparation aspects which influence how rapid a questionnaire can be administered. It is of vital importance that relevant organizations have existing validated questionnaires at their disposal. This review showed that in most studies existing questionnaires had to be modified to the specific disaster state of affairs. This indicates that modifying a questionnaire is possible and oftentimes necessary for rapid assessment. A second aspect of preparation is translation of the questionnaire, which is important whenever foreign speaking people are involved in the disaster. It saves fourth dimension to translate questionnaires at forehand in foreign languages which are common in a certain area. We assumed that if multiple aspects of preparation were present this peradventure tin can be too time-consuming for rapid cess. However, in two studies modification, translation and conducting the questionnaire was possible within the first 2 weeks [20, 27]. The data reported by Bayleyegn [20] was collected with assistance of a sufficient number of interviewers who were health professionals. This allowed completion of the survey in relative short fourth dimension. An American assessment team in the survey of Daley [27] recruited Turkish volunteers who helped review the Turkish version of the questionnaire later on an earthquake disaster in Turkey. This Turkish version of the questionnaire already existed and only the modifications needed to be translated.

Also the method of assessment used influences the rapidness of assessment. Almost studies used face to face interviews, which appeared to exist a quick method, because time tin be saved equally researchers tin can immediately collect the results. The responders tin can non cull their fourth dimension to fill in the questionnaire. A phone interview also gives straight admission to answers. It is important in rapid assessments that the researcher decides when the questionnaires are conducted and not the interviewee. In combination with the use of a computer that direct records the answers, the rapidness of assessment will exist increased. Considering the two registration methods dissimilar advantages were observed. Near of these studies used data from existing registrations, which can save time because researchers practise not actively demand to collect information; they only have to abstruse data and assign into categories. On the other manus, when information are actively recorded fourth dimension can exist saved because information are directly assigned into pre-chosen categories. An platonic state of affairs would be when data are straight recorded into a computer on a specific disaster class.

Collection of data at a central location with direct access to completed questionnaires is favourable. Therefore the choice of location besides contributes to the rapidness of conducting interviews. Location also influences travelling time of researchers. Assessment at a fundamental place (e.grand. an evacuation or research heart) is less-time consuming then interviewing people in their homes where researchers accept to go to different locations.

The level at which information is collected (east.g. at private or group level) is also an aspect that influences the fourth dimension information technology takes to perform an assessment. The modified cluster sampling method of the WHO [51] provides health data at household level. This is the most unremarkably used sampling method when using structured questionnaires to conduct rapid assessment of needs after natural disasters. This method is in particular useful with a geographically dispersed population. Cluster sampling divides the population into groups, or clusters. A number of clusters are selected randomly to stand for the evacuated population or an unabridged affected community. It is a representative method [20] and is less time-consuming than interviewing all disaster victims. Furthermore this sampling technique requires fewer resources. Information nerveless using registries is mostly collected at an individual level. When data is abstracted from existing registries data from thousands of persons can exist collected in a relative curt fourth dimension.

Considering source of information using registries it appeared that information was mostly registered by medical personnel. Half of the studies collected information specially for the purpose of health assessment later disaster, in the other studies registration was a standard procedure during medical consultation. When registration is a standard process, medical personnel do not need to invest extra time in data drove.

In brusk, we conclude that preparation of questionnaires and research, fourth dimension of measurement, choice of enquiry location, the method of assessment, level of assessment and extent of the survey are all important factors which may influence the rapidness of cess.

Aspects of rapid assessments which might add to or salvage the burden of disaster victims

An important topic that needs attending when collecting data after disasters is the burden of disaster victims. There is a growing recognition that collecting wellness data from the survivors should not aggravate their health. Ideally, a rapid assessment is needed which is the least demanding for disaster victims. After all, the master goal of health assessments is to collect information that supports the care of disaster survivors. Therefore nosotros will discuss the results in this light. To our noesis no literature exists that explicitly studies which aspects may influence the burden of survivors. We assume that the lower the number of survivors included in an assessment and the fewer the asked tasks for survivors, the lower the burden for the grouping as a whole or for the private. With this assumption the post-obit aspects of rapid assessments were observed which may add to or salve the burden.

1) The apply of data from existing registration systems. Nosotros observed that virtually all data was routinely collected past medical personnel independent of type of registration. This way affected people were not additionally burdened. Viewing registrations in this perspective, Stalling argued et.al [52] that researchers tin intrude into people's lives at the worst possible moments. Disaster researchers commonly justify intrusion to collect noesis with the aim to reduce suffering and amend response in futurity disasters. Notwithstanding the cost of this proceeds of noesis might exist disproportionally past subjects. This indication supports the utilise of existing registrations for health assessment. When information is collected with use of registrations no direct contact with survivors is needed. This ways that researchers do not have to intrude into the lives of survivors.

2) Location of cess may influence the try it takes for survivors to participate in a survey. Interviewing affected people in their ain homes or in evacuation centres, where they were located, might be less demanding than interviewing people outside their residence. Nevertheless, an advantage of a central identify to the survivors is that they have the possibility to meet neighbours and friends in particular after evacuation. This social component has been observed in the Netherlands; survivors were very positive well-nigh meeting friends and neighbours in a research eye. Personal contact with other survivors might contribute to restore individual well-beingness.

iii) Taking a representative sample of all disaster survivors when using questionnaires to collect information; fewer survivors need to exist burdened. However, survivors might experience excluded from participation in the study, in item if exposure is measured and survivors are worried nigh exposure. For each specific disaster situation the pros and cons need to be considered. In general for large scale disasters we recommend to utilise a sample size that has a reasonable margin of mistake.

four) The magnitude of research depends also on, for example, the length of a questionnaire; ideally the magnitude of inquiry should exist minimized in the rapid phase. Simply information that is immediately necessary, that needs to be collected quickly to minimize bias, or that might get otherwise lost, should just be considered in this phase.

An important question in this perspective is to what extent do assessments contribute to the survivors feeling of control over oneselves? Did information technology assistance them to salve the impact of the disaster? Later on the astute phase in which astute care is given, other health aspects might not have starting time priority because they might be primarily occupied with surviving. Nevertheless, assessments might positively contribute to the feeling of command in survivors because attention is paid to their needs. Anecdotally testify exists in the netherlands and from the CDC (Alden Henderson, personal communication) that disaster survivors experience information technology positively when their needs are addressed by a confront to face up interview. Disaster victims often evaluated this equally positive in that the government is paying attention to their needs. These questions deserve further inquiry. We recommend to interview survivors nigh this topic after approximately three-half dozen months post-disaster in focus groups. Results from this enquiry can serve as input for the development of the rapid assessment tool.

Literature and limitations

Our search strategy resulted in one.768 manufactures, more half of these studies were excluded because of our definition of disaster (n = 992). To minimize missing relevant articles nosotros had chosen a wide range of keywords related to disaster. Search terms such equally "traumatic issue" and "life event" appeared to be too general. As a upshot, many studies were excluded because they concerned individual events.

In this review we examined why health and needs assessments were excluded from this review considering of the criterion "rapid". The most important reason was that relevant information was missing in society to determine whether a rapid cess was possible. Often information was lacking virtually the menstruation in which the assessment took place and about its duration. Some articles did non draw information on how a questionnaire was conducted. If we did include all wellness and needs assessments, we probably would not have drawn different conclusions. About half of the studies which are excluded because of the 'rapid' criterion used questionnaires and about half of these studies used registries. Most of these studies as well performed assessments with use of face to face interviews and existing registries.

Although rapid assessment tools were developed for a broad range of emergencies (WHO & CDC) this review showed that rapid assessments were particularly conducted after natural disasters. The studies were in item performed after hurricanes with at least tens of thousands people involved. Although disasters of this scale inappreciably ever occur in Europe, we consider these studies to exist very informative for the development of a rapid cess tool, because we are principally interested in the method of assessment. These assessments could be used after different types of disasters and mass emergencies because every event has direct consequences for the public wellness intendance.

Publication bias could have affected our results; perchance many conducted rapid assessments were not published in peer-reviewed journals. Publishing articles might non have priority because the master goal of health and needs assessments is to collect data to back up the care and needs of the survivors. This principal goal also indicates that wellness and needs assessments should non be demanding for disaster victims. Surprisingly, the brunt of disaster victims seems no topic of discussion in the literature describing health assessments subsequently disasters.

Furthermore, in all reviewed manufactures information near processing time of the results is missing. This makes it difficult to guess the total duration of the assessments. Because of this, we cannot draw conclusions nearly when information is communicated to policy makers and health intendance providers. Information technology is important that data is analyzed quickly, so that results can be available as presently every bit possible [v]. In most of the studies information technology is also unclear whether newspaper or digital versions of questionnaires were used. Although nosotros assume digital versions of questionnaires increase the rapidness of an assessment, nosotros cannot draw conclusions about the influence of newspaper or digital versions of a questionnaire on the rapidness of an assessment. Also, none of the studies described their selection of data collection method. Therefore, we cannot discuss the considerations researchers make about their selection of data collection to make a rapid cess possible. Information technology was too unclear why assessments sometimes were performed in evacuee camps and sometimes in the nigh affected communities at people'south ain homes. We recommend author's of future papers to describe their methods more extensively on how and why a sure method is used and adult. In general we observed that a lot of NGO'southward who perform rapid assessments after disaster do non publish their findings. This is understandable because their master goal is the immediate relief of the needs of disaster survivors. Notwithstanding we recommend NGO'southward to publish their findings afterwards their principal goals are reached, considering we consider it very important to internationally share the lessons learned.

From the ten studies performed afterwards hurricane Katrina we learned that after a disaster of such enormous scale, several assessments in evacuation camps and in peoples own homes were necessary to get a consummate view of health condition and needs of affected people. It is possible that more rapid assessments were performed at unlike locations after other disasters also, merely that these were not published.

Finally, nosotros found that some studies compared data of registries with data from a reference grouping or reference period. In dissimilarity, none of the studies that used structured questionnaires compared their results with data from a reference group or reference period. Comparing with the same kind of data assessed pre-disaster is often not possible.

Conclusion & Recommendations

In conclusion, this review shows that questionnaires were primarily used to assess health needs and registries to assess wellness status. Questionnaires were likewise frequently used to assess health status, but registries were rarely used to assess health needs. In exercise, questionnaires are sufficient to assess wellness status and needs. Yet, to minimize the possible burden of survivors we prefer the apply of registries to appraise health status and needs if possible. The use of existing registries as well makes it possible to routinely collect information. Another reward of the utilize of existing registries is the possibility to compare the health condition in a disaster situation with a non-disaster situation. Comparison of data from registries provides longitudinally information well-nigh possible increase of illnesses, injuries or hospital visits due to the disaster. In general, the employ of reference data provides insight into the actual demand for wellness care and whether this demand is different or more extensive than the needs regular health organization ordinarily deals with. This may provide management for public health interventions. We also plant that with the use of registries a large number of participants tin be included in a survey, showing that registries tin can easily deal with a large amount of information. Nevertheless it is important to realise that it is non possible to internationally develop a standardized registration system, because the possibilities in each country are dissimilar. For example European countries have different types of wellness registries and different privacy rules to use the data for wellness inquiry purposes. Furthermore, this review showed that the well-nigh commonly used registries are hospital registration systems. When deriving the health status from infirmary registration systems only the nearly severe conditions will be institute. In the Netherlands, we have feel with an ongoing surveillance plan of health problems registered by general practitioners later a disaster [9, 10]. If the disaster did not disrupt the normal health structure, unremarkably people will visit their full general practitioner in stead of a infirmary. To preclude lack of data we recommend assessing also data from registries of general practitioners apart from hospital registrations. To employ these medical registries rapidly, grooming is essential.

Health needs can exist derived from wellness condition, for example which medications are needed. But not all needs can exist established with registries, for instance access to food and water and personal health needs other than medical necessities are of import to consider. To assess this kind of information a supplementary questionnaire is necessary. A questionnaire is also necessary in case access to existing registrations is non quickly possible.

Summarizing we recommend the employ of registries in combination with a brief questionnaire for rapid assessment of health condition and health needs. Development of this questionnaire needs to be advisedly prepared in a non-disaster situation. First the content needs to exist established and should be combined with (personal) exposure cess as much as possible [53]. Second, decisions should be fabricated about translations of the questionnaire to prepare for possible population groups. Third, it is of import that the researcher collects data directly; phone or face to face interviews are for this reason recommended for rapid cess. Furthermore, the method, use of questionnaire or existing registration, should be operational within two weeks post-disaster. Finally nosotros must be aware that if a large scale disaster with tens or hundreds of thousand evacuees strikes, several assessments in the beginning weeks mail service-disaster might be necessary.

Overall, it is important that the rapid assessment tool can be applied afterward all types of disaster when the regular health system is disrupted or overloaded. In general special attending should exist directed to vulnerable groups like people with pre-existing wellness conditions, significant women and vulnerable elderly. This is important because these sensitive subpopulations concern people with unique health needs. For instance, it can exist more difficult for them to evacuate after a disaster or to obtain access to the medical services they need [54, 55]. Beyond the issues of measurement we recommend the evolution of a standardized questionnaire which tin be used internationally. This makes it possible to compare the data that is unambiguous. Preferably one questionnaire will exist developed with different modules. This modules are sets of questions that can be modified to the specificity of the disaster state of affairs such equally blazon of disaster and country. A bones set of questions can be adult for each disaster situation, such as disaster involvement (e.thousand. rider or citizen) and the experiences and losses due to the disaster. This standardized questionnaire makes it possible to internationally compare the data that is unambiguous. This review summarizes the existing questionnaires which can serve as a starting point to develop a standardized questionnaire.

References

-

Van den Berg B, Grievink L, Gutschmidt Chiliad, Lang T, Palmer S, Ruijten Grand, Stumpel R, Yzermans J: The Public Health Dimension of Disasters - Wellness Outcome Assessment of Disasters. Prehospital Disast Med. 2008, 23 (Suppl 2): 55-59.

-

Roorda J, van Stiphout WA, Huijsman-Rubingh RR: Post-disaster health effects: strategies for investigation and data drove. Experiences from the Enschede firework disaster. J Epidemiol Customs Health. 2004, 58: 982-987. 10.1136/jech.2003.014613.

-

Tailhades M, Toole MJ: Disasters: what are the needs? How tin they be assessed?. Trop Doc. 1991, 21: 18-23.

-

CDC: Rapid community needs assessment after hurricane Katrina-Hancock County, Mississippi, September 14-15, 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 234-236.

-

WHO: Rapid Health Assessment Protocols for Emergencies. WHO, Geneva. 1999, 103-

-

CDC: Tropical storm Allison rapid needs assessment--Houston, Texas. MMWR. 2002, 51: 365-369. June 2001

-

CDC: Rapid health response, assessment, and surveillance afterward a Tsunami-Thailand. MMWR. 2005, 54: 61-64. 2004-2005

-

van Kamp I, van der Velden PG, Stellato RK, Roorda J, van Loon J, Kleber RJ, et al: Physical and mental wellness soon after a disaster: kickoff results from the Enschede firework disaster report. Eur J Public Health. 2006, xvi: 253-259. x.1093/eurpub/cki188.

-

Yzermans CJ, Donker GA, Kerssens JJ, et al: Wellness Problems of victims earlier and subsequently disaster: a longitudinal report in general practise. International Periodical of Epidemiology. 2005, 34: 820-826. ten.1093/ije/dyi096.

-

Dorn T, Yzermans CJ, Kerssens JJ, et al: Disaster and subsequent healthcare utilization: a longitudinal study among victims, their family members, and control subjects. Medical Care. 2006, 44: 581-589. x.1097/01.mlr.0000215924.21326.37.

-

American Psychiatric Association: DSM-4-TR: Diagnostic Statistic Manual of Mental Disorder. American Psychiatric Clan. 2000, 943-

-

Greenough PG, Lappi MD, Hsu EB, Fink S, Hsieh Y, Vu A, Heaton C, Kirsch T: Burden of Disease and Health Status Amidst Hurricane Katrina-Displaced Persons in Shelters: A Population-Based Cluster Sample. Ann Emerg Med. 2008, 51: 426-432. ten.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.04.004.

-

Ghosh TS, Patnaik JL, Vogt RL: Rapid needs assessment among Hurricane Katrina evacuees in metro-Denver. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007, 18: 362-368. ten.1353/hpu.2007.0030.

-

Ridenour ML, Cummings KJ, Sinclair JR, Bixler D: Deportation of the underserved: medical needs of Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Due west Virginia. J Health Intendance Poor Underserved. 2007, eighteen: 369-381. 10.1353/hpu.2007.0045.

-

Schnitzler J, Benzler J, Altmann D, Mucke I, Krause Thousand: Survey on the population's needs and the public health response during floods in Federal republic of germany 2002. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007, 13: 461-464.

-

CDC: Assessment of Health-Related Needs After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita-Orleans and Jefferson Parishes, New Orleans Surface area, Louisiana, Oct 17-22, 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 38-41.

-

CDC: Rapid needs assessment of ii rural communities after Hurricane Wilma -Hendry County, Florida, November 1-2, 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 429-431.

-

CDC: Rapid assessment of wellness needs and resettlement plans among Hurricane Katrina evacuees--San Antonio, Texas, September 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 242-244.

-

CDC: Rapid community needs assessment after hurricane Katrina-Hancock Canton, Mississippi, September 14-fifteen, 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 234-236.

-

Bayleyegn T, Wolkin A, Oberst Yard, Young S, Sanchez C, Phelps A, et al: Rapid assessment of the needs and health status in Santa Rosa and Escambia counties, Florida, later Hurricane Ivan, September 2004. Disaster Manag Response. 2006, 4: 12-18. x.1016/j.dmr.2005.10.001.

-

Rodriguez SR, Tocco JS, Mallonee S, Smithee L, Cathey T, Bradley K: Rapid needs assessment of Hurricane Katrina evacuees-Oklahoma, September 2005. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006, 21: 390-395.

-

Brennan RJ, Rimba K: Rapid wellness cess in Aceh Jaya District, Indonesia, following the December 26 tsunami. Emerg Med Australas. 2005, 17: 341-350. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2005.00755.x.

-

CDC: Rapid community wellness and needs assessments after Hurricanes Isabel and Charley--N Carolina, 2003-2004. MMWR. 2004, 53: 840-842.

-

CDC: Rapid Assessment of the Needs and Health Status of Older Adults After Hurricane Charley - Charlotte, DeSoto, and Hardee Counties, Florida, August 27-31, 2004. MMWR. 2004, 53: 837-840.

-

Chen KT, Chen WJ, Malilay J, Twu SJ: The public wellness response to the Chi-Chi convulsion in Taiwan, 1999. Public Wellness Rep. 2003, 118: 493-499.

-

CDC: Community Needs Assessment of Lower Manhattan Residents Post-obit the World Trade Center Attacks - Manhattan, New York City, 2001. MMWR. 2002, 51 (Special): ten-xiii.

-

Daley WR, Karpati A, Sheik Thou: Needs assessment of the displaced population following the August 1999 earthquake in Turkey. Disasters. 2001, 25: 67-75. 10.1111/1467-7717.00162.

-

CDC: Customs needs assessment and morbidity surveillance following an ice tempest - Maine, January 1998. MMWR. 1998, 47: 351-354.

-

CDC: Surveillance for injuries and illnesses and rapid health-needs cess post-obit Hurricanes Marilyn and Opal, September-Oct 1995. MMWR. 1996, 45: 81-85.

-

CDC: Comprehensive Assessment of Health Needs 2 Months later Hurricane Andrew - Dade County, Florida 1992. MMWR. 1993, 42: 434-437.

-

CDC: Rapid health needs assessment following hurricane Andrew--Florida and Louisiana, 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992, 41: 685-688.

-

Cookson ST, Soetebier K, Murray EL, Fajarda GC, Hanzlick R, Drenzek C: Internet-Based Morbidity and Mortality Surveillance Amidst Hurricane Katrina Evacuees in Georgia. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008, v (four):

-

CDC: Monitoring Health Effects of Wildfires Using the BioSense System - San Diego County, California, October 2007. MMWR. 2008, 57: 741-747.

-

Brown SH, Fischetti LF, Graham One thousand, Bates J, Lancaster AE, McDaniel D, et al: Use of electronic health records in disaster response: the experience of Department of Veterans Affairs after Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Wellness. 2007, 97: 136-141. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.104943.

-

Jhung MA, Shehab N, Rohr-Allegrini C, Pollock DA, Sanchez R, Guerra F, et al: Chronic disease and disasters medication demands of Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Am J Prev Med. 2007, 33: 207-210. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.030.

-

Sullivent EE, Due west CA, Noe RS, Thomas KE, Wallace LJ, Leeb RT: Nonfatal injuries following Hurricane Katrina--New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005. J Safety Res. 2006, 37: 213-217. ten.1016/j.jsr.2006.03.001. III

-

CDC: Illness Surveillance and Rapid Needs Assessment Amongst Hurricane Katrina Evacuees - Colorado, September 1-23, 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 244-247.

-

CDC: Surveillance for Illness and Injury After Hurricane Katrina - Iii Counties, Mississippi, September v - October 11, 2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 231-234.

-

CDC: Rapid assessment of injuries amongst survivors of the terrorist assail on the Earth Trade Center --New York City, September 2001. MMWR. 2002, 51: one-5.

-

Ogden CL, Gibbs-Scharf LI, Kohn MA, Malilay J: Emergency health surveillance after astringent flooding in Louisiana, 1995. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2001, 16: 138-144.

-

CDC: Injuries and illnesses related to Hurricane Andrew--Louisiana, 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993, 42: 242-251.

-

Lee LE, Fonseca V, Brett KM, Sanchez J, Mullen RC, Quenemoen LE, Groseclose SL, Hopkins RS: Active Morbidity Surveillance Afterwards Hurricane Andrew - Florida, 1992. JAMA. 1993, 270: 591-594. 10.1001/jama.270.5.591.

-

Bradt DA, Drummond CM: Rapid epidemiological cess of health status in displaced populations--an evolution toward standardized minimum, essential information sets. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2002, 17: 178-185.

-

Woersching JC, Snyder AE: Earthquakes in El Salvador: a descriptive report of health concerns in a rural customs and the clinical implications, part I. Disaster Manag Response. 2003, 1: 105-109. 10.1016/S1540-2487(03)00049-X.

-

Kwanbunjan K, Mas-ngammueng R, Chusongsang P, Chusongsang Y, Maneekan P, Chantaranipapong Y, et al: Wellness and nutrition survey of tsunami victims in Phang-Nga Province, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Wellness. 2006, 37: 382-387.

-

Finau SA: Health and nutritional condition of Tongan preschool children subsequently Cyclone Isaac. NZ Med J. 1986, 99: 630-632.

-

Dhara VR, Dhara South, Acquilla SD, Cullinan P: Personal Exposure and Long-Term Health Furnishings in Survivors of the Union Carbide Disaster at Bhopal. Environ Wellness Perspect. 2002, 110: 487-500. x.1289/ehp.02110487.

-

Havenaar J, Rumyantzeva G, Kasyanenko A, Kaasjager K, Westermann A, van den Brink W, van den Bout J, Savelkoul J: Health Effects of Chernobyl Disaster: Illness or Affliction Behavior? A Comparative General Wellness Survey in Two Former Soviet Regions. Environ Health Perpect. 1997, 105 (Suppl 6): 1533-1537. 10.2307/3433666.

-

Herbert R, Moline J, Skloot One thousand, Metzger Thou, Baron S, Luft B, Markowitz Due south, Udasin I, Harrison D, Stein D, Todd A, Enright P, Stellman JM, Landrigan PJ, Levin SM: The World Trade Center disaster and the wellness of workers: five-year cess of a unique medical screening program. Environ Health Perspect. 2006, 114: 1853-1858.

-

Alexander D: Illness Epidemiology and Earthquake Disaster: the example of southern Italy after the 23 November 1980 earthquake. Soc Sci Med. 1982, sixteen: 1959-1969. 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90399-ix.

-

Malilay J, Flemish region WD, Brogan D: A modified cluster-sampling method for mail-disaster rapid assessment of needs. Balderdash Word Health Organ. 1996, 74: 399-405.

-

Rodriguez H, Quarantelli EL, Dynes RR: Handbook of disaster research. Springer. 2007, 643-

-

Bongers S, Janssen NAH, Grievink Fifty, Lebret E, Kromhout A: Challenges of exposure cess for health studies in the backwash of chemical incidents and disasters. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. 2008, 00: 1-19.

-

Holt JB, Mokdad A, Ford ES, Simoes EJ, Bartoli WP, Mensah GA: Use of BFRSS Data and GIS Technology for Rapid Public Wellness Response During Natural Disasters. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008, 5: one-18.

-

Dyer CB, Regev M, Burnett J, Festa Due north, Cloyd B: SWIFT: a rapid triage tool for vulnerable older adults in disaster situations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008, two: 45-fifty. x.1097/DMP.0b013e3181647b81.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this newspaper can exist accessed here:http://world wide web.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/x/295/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors' wish to give thanks everyone who gave value comments on the draft manuscript from the National Institute for Public Health and the Surroundings and from the netherlands Health Institute for Health Services Inquiry. The author's would besides like to thank Wim ten Have for helping them with the development of the search strategy and for searching the different databases.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Boosted information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HAK selected the literature with assistance of IvB and LG. HAK interpreted and analyzed the literature and as well drafted the manuscript. All authors' critically reviewed and approved draft versions and the concluding manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12889_2009_2206_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Assessments conducted with use of questionnaires. Overview and characteristics of included articles. (DOC 76 KB)

12889_2009_2206_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Boosted file ii: Assessments conducted with apply of registries. Overview and characteristics of included manufactures. (DOC 75 KB)

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open up Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Korteweg, H.A., van Bokhoven, I., Yzermans, C. et al. Rapid Health and Needs assessments after disasters: a systematic review. BMC Public Health x, 295 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-295

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/1471-2458-10-295

Keywords

- Rapid Assessment

- Registration Arrangement

- Digital Version

- Disaster Situation

- Disaster Victim

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-10-295